Typeface Terminology

the above was blogged from- http://www.fontshop.com/glossary/

History of Type:

Type Classification:

Humanist | Old Style | Transitional | Modern

Slab Serif (Egyptian) | Sans Serif

The Humanist types (sometimes referred to as Venetian) appeared during

the 1460s and 1470s, and were modelled not on the dark gothic scripts

like textura, but on the lighter, more open forms of the Italian humanist writers. The Humanist types were at the same time the first roman types.

So what makes Humanist, Humanist? What distinguishes it from other styles? What are its main characteristics?

1 Sloping cross-bar on the lowercase “e”;

2 Relatively small x-height;

2 Relatively small x-height;

3 Low contrast between “thick” and “thin” strokes (basically that means that there is little variation in the stroke width);

4 Dark colour (not a reference to colour in the traditional sense, but the overall lightness or darkness of the page). To get a better impression of a page’s colour look at it through half-closed eyes.

4 Dark colour (not a reference to colour in the traditional sense, but the overall lightness or darkness of the page). To get a better impression of a page’s colour look at it through half-closed eyes.

Old Style (or Garalde) types start to demonstrate a greater

refinement—to a large extent augmented by the steadily improving skills

of punchcutters. As a consequence the Old Style types are characterised

by greater contrast between thick and thin strokes, and are generally

speaking, sharper in appearance, more refined. You can see this, perhaps

most notably in the serifs: in Old Style types the serifs on the ascenders are more wedge shaped (figure1.1).

Another major change can be seen in the stress of the letterforms

(figure 1.2) to a more perpendicular (upright) position. You may

remember our old friend, the lowercase e of the Humanist

(Venetian) types, with its distinctive oblique (sloping) crossbar; with

Old Style types we witness the quite sudden adoption of a horizontal

crossbar (figure 1.3). I spent quite a time trying to discover why the

lowercase e should change so dramatically. After searching high

and low, and opening just about every type book I own, I decided to

post the question on Typophile. Space doesn’t permit to recount the

entire tale here, but for those interested in such details, then head on

over to the Typophile e crossbar thread. (Thanks to Nick Shinn, David et. al. for their valuable input).

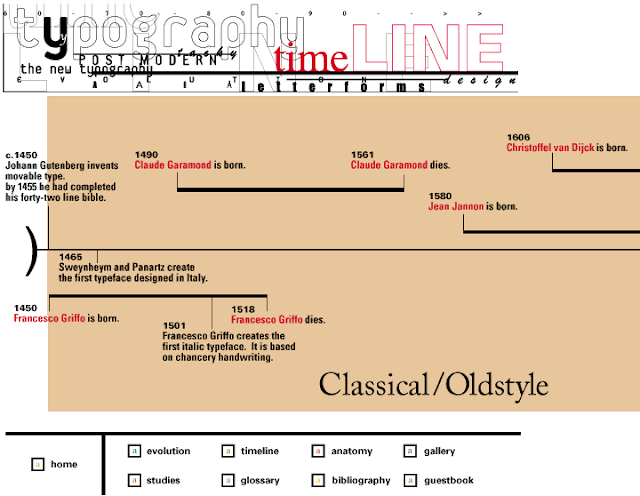

The First Italic Type

And, as we’re on the topic of dramatic changes, during this period we

see the very first italic type in 1501. They were first created, not as

an accompaniment to the roman, but as a standalone typeface designed

for small format or pocket books, where space demanded a more condensed

type. The first italic type, then, was conceived as a text face.

Griffo’s contribution to roman type include an improved balance between capitals and lowercase, achieved by cutting the capitals slightly shorter than ascending letters such as b and d, and by slightly reducing the stroke weight of the capitals.

—A Short History of the Printed Word, Chappell and Bringhurst, page 92

The Old Style types can be further divided into four categories as in the figure below, and span the roman types from Francesco Griffo to William Caslon I.

Unlike the relatively short-lived Humanist faces, the Old Style faces

held sway for more than two centuries; a number of them are still

popular text faces today.

Transitional Typefaces

Today we’ve moved along the time-line to the cusp of the 18th

century, the start of a period in history that we now refer to as the The Enlightenment,

a time that was to sow the seeds of revolution in France, North America

and beyond. But today we stand in the cobbled streets of 17th century

France; Louis XIV is on the throne and Jacques Jaugeon is working on

what is now considered to be the first Transitional (or Neoclassical)

style typeface, the Romain du Roi or King’s Roman, commissioned by Louis XIV for the Imprimerie Royale in 1692.

The Romain du Roi marked a significant departure from the former Old Style types and was much less influenced by handwritten letterforms. Remember, this is the Age of the Enlightenment, marked by resistance to tradition, whether that be art, literature, philosophy, religion, whatever; so it’s no surprise that this same era should give birth to radically different types.

The Romain du Roi is often referred to as Grandjean’s type,

but the designs were produced by a committee* set up by the French

Academy of Science. One of the committee members, Jacques Jaugeon — at

that time better known as a maker of educational board games — in

consultation with other members, produced the designs constructed on a

48×48 grid (2,304 squares). The designs — also known as the Paris Scientific Type

— were engraved on copper by Louis Simmoneau, and then handed to the

punchcutter Grandjean (not to be confused with the earlier Granjon of

course), who began cutting the type in 1698. Interestingly, Jaugeon also

designed a complimentary sloping roman (often referred to today as an

oblique) as an alternative to a true italic**. However, Grandjean

himself was to produce the italic from his own designs.

The principal graphic novelty in the

‘Romain du Roi’ is the serif. Its horizontal and unbracketed structure

symbolizes a complete break with the humanist calligraphic tradition.

Also, the main strokes are thicker and the sub-strokes thinner…. — Letter Forms, page 23, Stanley Morison

The first book to use these types wasn’t published until a decade

later in 1702. In fact the full set of 82 fonts wasn’t completed until

half a century later in 1745.

[Baskerville] was not an inventor but a perfector…. He concentrated on spacing. He achieved amplitude not merely by handsome measurement but by letting in the light.—Type, the Secret History of Letters, Simon Loxley, page 54 (quoting from English Printed Books)

“Baskerville has less calligraphic flow than most earlier

typefaces”***, and this can be said of just about all the Transitional

Style types. Whereas the earlier Humanist and Old Style types owed much

to the handwritten letter form, the pen’s influence has all but

disappeared in the Transitional types. The following is a detail from

one of Baskerville’s type specimens:

3 Head serifs generally more horizontal:

No comments:

Post a Comment